The Vermont Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in six cases during the high court's annual session at Vermont Law School on Wednesday, March 8, in Oakes Hall on the VLS campus. The session is open to the public. Vermont Court Rules apply for media coverage.

The court will consider the following cases:

In re Hinesburg Hannaford Act 250 Permit and In re Hinesburg Hannaford Site Plan Approval, docket numbers 16-273 and 16-274 (9:30 to 10:30 a.m.)

Whether a proposed Hannaford Supermarket complies with local zoning regulations and Act 250. That is the question. The environmental court thought so and approved the project, subject to some conditions, but a group of Hinesburg residents believe this was the wrong decision. On appeal, the residents argue that the proposed supermarket interferes with setback requirements, stormwater management, neighborhood aesthetics, and their use of a nearby canal path. The Town of Hinesburg doesn't challenge the whole plan, but claims Hannaford must conduct a traffic study after building the supermarket. By contrast, Hannaford asks the Supreme Court to affirm the environmental court's decision, except for a condition requiring installation of a traffic signal.

State v. Gregory Manning, docket number 16-141 (11 to 11:30 a.m.)

Gregory Manning appeals his conviction of embezzlement of roughly $10,000 from his employer, the Corner Stop Mini Mart in South Royalton. At trial, the State alleged that Mr. Manning had been tasked with depositing cash from the Corner Stop into a local bank's deposit box, but that video footage from inside the bank showed that, on several occasions, Mr. Manning either simply approached the deposit box without placing anything in it or merely pretended to put the cash in the box. The bank therefore never received the cash, and the amounts never appeared on the Corner Stop's bank statements. Importantly, the footage was not preserved before trial, and Mr. Manning's appeal largely stems from this failure to preserve the footage. He argues that the case against him should have been dismissed because the State failed to secure a warrant to preserve the footage and because the State should have been barred from presenting evidence regarding the footage. Mr. Manning also argues that the State's closing argument improperly shifted the burden to preserve evidence and improperly impugned his trial strategy. Finally, Mr. Manning argues that the trial court's requirement that he complete a Restorative Justice Program as part of his sentence was improper because the requirement was not individually tailored to his particular circumstances.

State v. William D. Schenk, docket number 16-166 (11:30 a.m. to noon)

When Klu Klux Klan recruitment fliers are left at the homes of two minority women, can the State prosecute distribution of the fliers as disorderly conduct? The State charged William Schenk with two counts of "recklessly creat[ing] a risk of public inconvenience or annoyance when he engaged in threatening behavior … by anonymously placing a flyer endorsing the Klu Klux Klan" in violation of 13 V.S.A. § 1026(a)(1), Vermont's disorderly conduct statute. Mr. Schenk appeals his conviction for those two counts, as well as a sentence enhancement for violation of the State's hate crime statute. He argues that the charged provision of the disorderly conduct statute only applies to physical behavior, not speech, but that, if the statute can be applied to speech, then the law is content-based and requires strict scrutiny review to determine whether it withstands the presumption of invalidity. Mr. Schenk also argues that even if the statute is facially valid, distribution of the Klu Klux Klan fliers here does not fall into the true threats category of unprotected speech because a true threat requires specific intent to put a person in fear of imminent harm.

State v. Rebekah S. VanBuren, docket number 16-253 (1:30 to 2 p.m.)

This case concerns the constitutionality of 13 V.S.A. § 2606—Vermont's "revenge porn" statute—which was enacted in 2015. Here, Rebekah VanBuren's boyfriend received nude selfies through his Facebook account from the complainant. Because Ms. VanBuren's boyfriend remained logged-into Facebook on Ms. VanBuren's cell phone, she accessed his Facebook and discovered the photos. Ms. VanBuren then published the photos publicly on Facebook, tagging the complainant. After the State charged Ms. VanBuren with a misdemeanor violation of 13 V.S.A. § 2606, she moved to dismiss. The trial court granted the motion, holding that the statute not only was subject to strict scrutiny but also violated the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. On appeal, the State now argues that the trial court erred because publicly disseminating someone's private nude photos without their consent is not constitutionally protected expression, and, even if it were, 13 V.S.A. § 2606 is nevertheless constitutional because it directly advances the State's compelling interest in protecting the privacy, sexual consent, and reputations of its citizens and is not unduly restrictive.

Grant Taylor and Richard Scheiber v. Town of Cabot, Cabot Community Association, and United Church of Cabot, Inc., docket number 16-276 (2 to 2:30 p.m.)

Do municipal taxpayers have standing to challenge the use of funds that originated from a federal grant and did not come from municipal tax revenues when the town gives those funds to a church for the purpose of renovating the church building? Did a trial court properly grant a preliminary injunction to those taxpayers who challenged the use of the funds on the grounds that it violated the Compelled Support Clause of the Vermont Constitution, which prohibits state funds from being used to support religious worship? In the 1980s, the federal government awarded the Town of Cabot a $2 million grant. Cabot loaned a local co-op the entire $2 million to construct new facilities. The co-op fully repaid the loan in 2003, and this money was set aside in a fund that is separate from other municipal resources. According to the agreement that Cabot made with the federal government, it could keep this money and use it for projects that would have been eligible for federal grants under the Housing and Community Development Act. This law prohibits grant funds from advancing "inherently religious activities," but does allow funds to go toward religious structures if not used for inherently religious activities. In 2015, the United Church of Cabot applied to the town for $10,000 out of the fund because its church was in need of repair, and the town granted the request. Members of the community filed a complaint to enjoin the town from distributing the funds to the Church. The town filed a motion to dismiss for lack of standing, claiming that the funds involved did not originate from municipal taxpayers and therefore the plaintiffs cannot claim taxpayer standing. The trial court denied the motion to dismiss and then granted the plaintiff's request for a preliminary injunction. The town then filed for permission to file an interlocutory appeal with the Supreme Court, which the court granted.

Shires Housing, Inc. v. Carolyn Brown, docket number 16-323 (2:30 to 3 p.m.)

What notice must a mobile home park owner give to a tenant prior to initiating eviction proceedings against the tenant when the tenant engages in a substantial violation of the terms of their lease? Carolyn Brown lived in a mobile home in a park owned by Shires Housing. Shires Housing initiated eviction proceedings against Ms. Brown immediately after it became aware that her cotenant had been arrested and charged with illegal drug use in the mobile home, which the parties agree was a substantial violation of Ms. Brown's lease terms. The statutes that govern when a mobile home park owner may initiate eviction proceedings require that the owner provide notice to a tenant six months prior to initiating eviction proceedings, except that "[a] substantial violation of the lease terms . . . may result in immediate eviction proceedings." However, the agency charged with carrying out those statutes and making rules regarding mobile home regulation, the Department of Housing and Community Development, has enacted a rule that requires the park owner to provide notice within six months of a substantial violation. Ms. Brown argues that the statute is ambiguous as to what notice is required for a substantial violation and the agency's rule interpreting the statute therefore controls, meaning that notice is required for a first—but not second—uncured substantial violation. Shires Housing argues that the statute is clear and that no notice is required for a substantial violation.

###

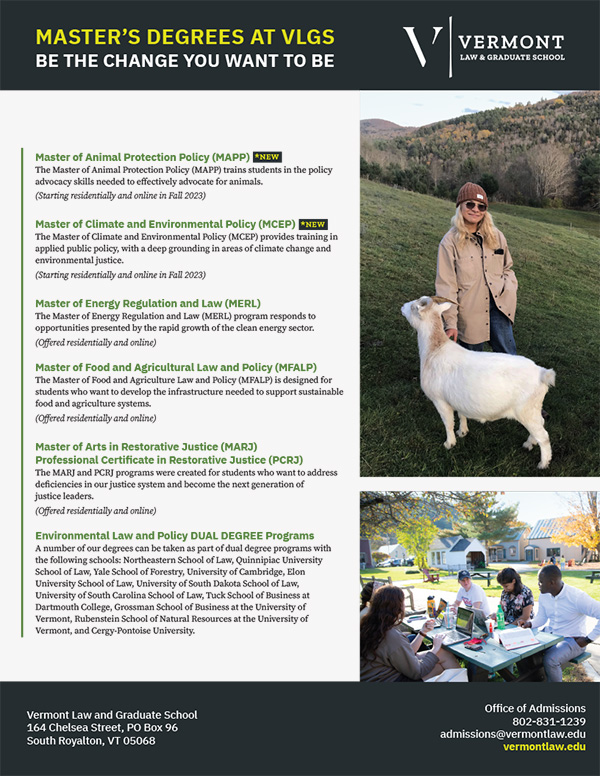

Vermont Law School, a private, independent institution, is home to the nation's largest and deepest environmental law program. VLS offers a Juris Doctor curriculum that emphasizes public service; three Master's Degrees—Master of Environmental Law and Policy, Master of Energy Regulation and Law, and Master of Food and Agriculture Law and Policy; and four post-JD degrees —LLM in American Legal Studies (for foreign-trained lawyers), LLM in Energy Law, LLM in Environmental Law, and LLM in Food and Agriculture Law. The school features innovative experiential programs and is home to the Environmental Law Center, South Royalton Legal Clinic, Environmental and Natural Resources Law Clinic, Energy Clinic, Food and Agriculture Clinic, and Center for Applied Human Rights. For more information, visit vermontlaw.edu, find us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.